Hip hop has traveled a long way since it first came to fruition on the streets of New York more than 35 years ago. What commenced as block party boredom has since blossomed into a $10 billion dollar industry spanning everything from soft drinks to perfume. But for those of us that grew up during hip hop’s early years, it isn’t what it used to be.

The precise “golden age” of hip hop is, of course, a debate unlikely to be resolved any time soon. To some, it’s the ‘80s. To others, it’s the ‘70s. But for me, there is no debate. The golden era will always be the late ‘80s through the early ‘90s, as the U.S. witnessed the mainstream emergence of West Coast rap.

West Coast rap was more than just funky bass lines, synths, and Zapp & Roger inspired talk boxes. It was a lifestyle—an open journal—an unapologetic commentary on the state of the streets. It was, for lack of a better term, “gangster.” It embodied the kind of shoes you wore, the kind of car you drove, and even how you drove it.

Admittedly, some of this is nostalgia on my part. I grew up during the 90s. I remember listening to It Was a Good Day by Ice Cube while cruising in my pearl ’67 Impala. I remember polishing my Chuck Taylors and bright white Nike Cortezes before hitting up the market or neighborhood house party.

Emcees on the East Coast didn’t stitch their street names in Old English across the back of their sweatshirts. Emcees in the Deep South didn’t know about Locs and Cascades. All of these things were uniquely West Coast. And like it or not, the West Coast was unlike anywhere else in the world, a unique blend of Black and Chicano culture. It was new school—with an oldie twist.

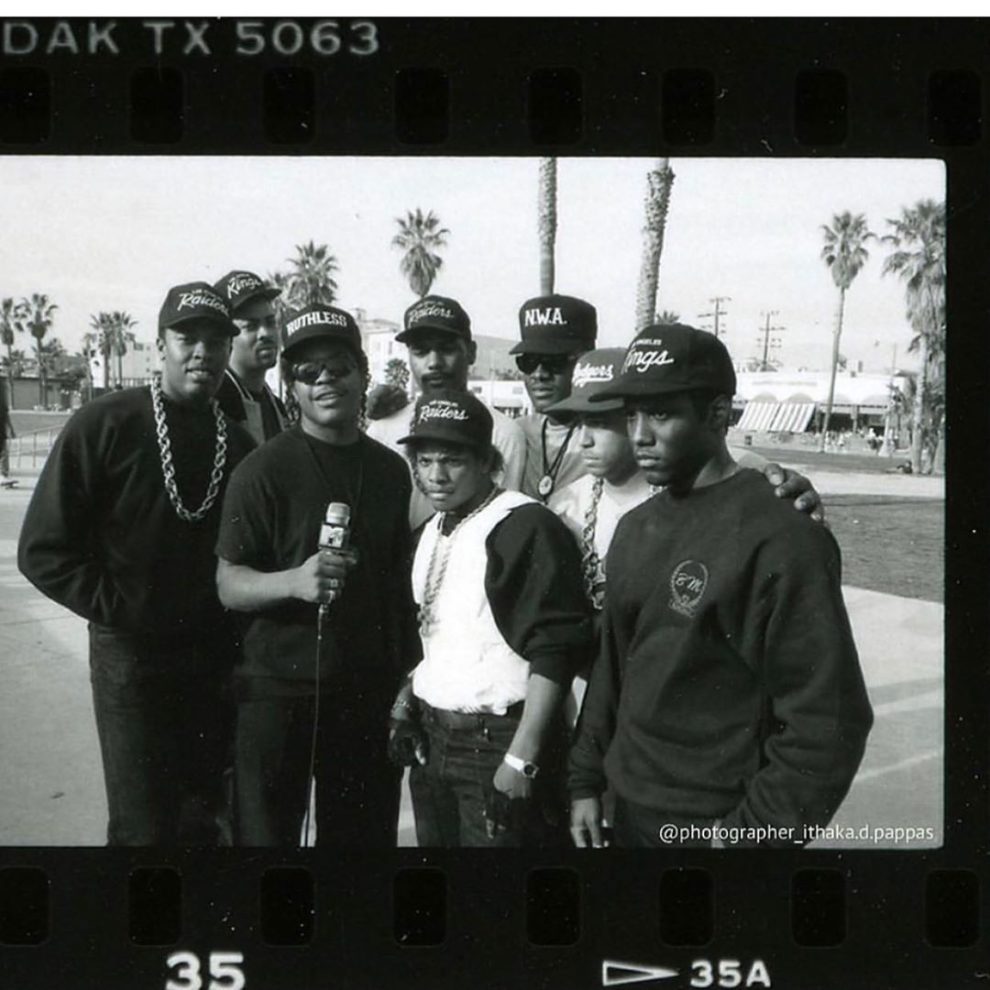

It was everywhere. In Compton, Eazy-E and DJ Quik blended ‘70s funk with the hardship of the ghetto. In East Los Angeles, Kid Frost kicked jams with Rick James. And in Pico Union, Psycho Realm blended ‘50s melodies with the sensibilities of the barrio.

Even metal bands like Suicidal Tendencies burst onto the music scene wielding a noticeable West Coast twist.

The artistic emphasis on life in the streets also wasn’t exclusive to Los Angeles. In the Bay Area, E-40, Too Short, and Rappin’ 4-Tay dominated the radio waves. In San Diego, Knightowl, Lil Rob, and Mr. Shadow, dominated the clubs.

But today one would be hard pressed to find an entire album laid back enough to barbecue or cruise to on a Saturday afternoon. On one hand, melodies of the “g-funk” era have given way to the pulsating rhythms of the club era (at least before COVID-19). On the other, Ben Davis and Dickies have given way to Instagram posers and skinny jeans.

What happened?

Help support Chicano/Latino Media. Subscribe for only $1.00 your first month.

For years, a handful of artists, primarily Kendrick Lamar and Nipsey Hussle, have been tasked with carrying the torch. But with Nipsey Hussle gone, and a younger generation gravitating toward newer genres like mumble rap, there are few—if any—notable West Coast artists left to carry the sonic legacy of traditional West Coast rap on a mainstream level.

This doesn’t mean the beats and sounds that once defined West Coast rap don’t still thrive in niche circles. They do. What it does mean, however, is that few of those artists have managed to breakout beyond the imaginary confines of the West Coast.

Were the ‘90s really just another era? Is “mumble rap” really the best successor Millennials and Gen-Z could come up with?

Without a doubt, the decline of mainstream West Coast hip hop has been nothing short of remarkable. However, the more I think about it, the more I’m also convinced it’s not entirely a bad thing.

While one would be hard pressed to deny the impact groups like NWA had on mainstream music, the explosion of West Coast rap during the 90s also led to an explosion of halfhearted copycats and emulators, many who lacked proper context and understanding of West Coast culture.

As a result, the media often focused more on the gangs and violence of the West Coast than the unique social, economic, and political landscape bubbling below the surface. Yet it was the influence of this landscape that truly made West Coast rap what it was.

The mainstreaming of West Coast culture also led to a watering down of the rawness that once gave it edge. Like the fusion of punk rock and metal further north—pioneered by late Nirvana frontman, Kurt Cobain—record labels swooped in, refined it, renamed it (“grunge”), packaged it, and sold it until consumers were fatigued.

Today, Chicano rap arguably bares the closest resemblance to traditional West Coast rap of any sub-genre. This is particularly true of newer artists like Misfit Soto or CNG, who have deliberately made an effort to shatter the traditional mold, while retaining all of the familiar West Coast elements.

In addition, artists like Fingazz and MC Magic have built entire careers off utilizing keyboards and talk-boxes. To this extent, many of the traditional elements of West Coast rap continue to dominate the West Coast underground, even if it isn’t considered “mainstream” to the rest of the country.

Or maybe West Coast rap will never be what it was. Its prime has come and gone. Nobody is destined to restore or save it. And only those who were lucky enough to be there will ever truly appreciate what it was.

After all, as hectic as it might seem sometimes, the world has come a long way since the 90s.

In either case, it’s been a fantastic voyage.

Get Columns Like This In Your Inbox

To receive weekly updates like this in your inbox, subscribe to The Daily Chela newsletter here.