The iconic 2002 Brazilian film, Cidade de Deus (City of God) is a stellar example of how to portray tragic and gruesome events through a narrative that brings the audience into its world.

This piece is the second in my series of articles that examine and review some of the most significant Latino films of the past couple decades. In the first article, I discussed the lack of Latino representation in U.S. films and analyzed the film, La Mission, delving into its themes and implications. For this film, I will focus more on the way Cidade de Deus tells its narrative and results of those methods.

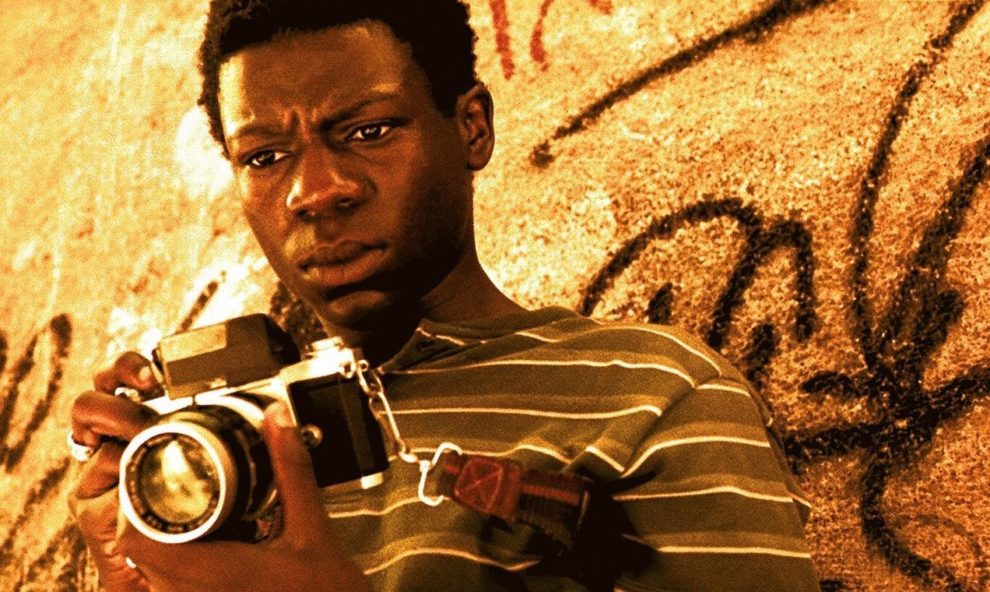

Directed by Fernando Meirelles and based on Paulo Lins novel, Cidade de Deus is based on true events from the 70s and 80s at the height of a drug war in the City of God, a favela (Brazilian slum) in Rio de Janeiro. The filmtells its story through the eyes of prospective photographer, Buscapé, translated in English to “Rocket.” The film is split up into several chapters the traverse the history of the City of God and stories of its people.

Important to note early on, the majority of those depicted as residents of the City of God are Black. Moreover, many of the police officers and business owners are of a lighter complexion. This obvious divide speaks to racialized poverty and the oppression that Black Latinos face. Colorism in Latin America is most obvious in these areas of extreme poverty and this film helps to expose that truth.

Brazilian Poverty and Violence

The film begins by recounting significant events from the characters’ early life. Though a young child at the time, Rocket’s neighbor Li’l Dice tries to keep up with the local gang of teenagers. After the gang disintegrates, Li’l Dice uses what he learned and continues to steal and murder to survive.

With his more amicable friend, Bené, by his side, Li’l Dice renamed Li’l Zé in adulthood, grows up to become the most powerful kingpin in the City of God. After Bené gets shot by a previously powerful drug lord who actually meant to kill Li’l Zé, an all-out drug war emerges. The streets soon filled with the bodies of both men and young boys.

The death toll was so high that public media was forced to take notice, while previously they ignored violence in that area given its prevalence. The intensity of the violence also encouraged public officials to finally intervene. Unfortunately, corruption within the police force ensured that the help they offered was minimal.

Though this is a Brazilian film, Cidade de Deus was well received by U.S. audiences and global audiences alike. For that reason, it is not only deserving of a spot in the canon of significant Latino cinema but also of cinema as a whole. In fact, Cidade de Deus received a 91% average on Rotten Tomatoes and is listed on several best films lists from media outlets like Empire, TIME, The Guardian, and Film4. Furthermore, the film won fifty-five awards and received twenty-nine nominations around the world.

That is not to say the film was well received by all critics. In 2011, top critic for the Chicago Reader, J. R. Jones said though the film had narrative control, he was “unmoved by anything it had to say,” further explaining that the critical acclaim the film received was due to the “nonstop action and astonishing body count.”

Though I would argue against this perspective, given that the inability to look beyond the gore and perceive significance, relies more so on the viewer, backed by the fact that many reviewers were able to extract complex meaning from the film.

However, Cidade de Deus did receive valid criticism that I believe must be spotlighted. Brazilian film critic, Ivana Bentes, posited that the rise in tourism after the film released, spoke to the idealized portrayals in the film that position Brazilian poverty and violence as products to be exported. I will further explore this criticism later.

Maintaining Authenticity

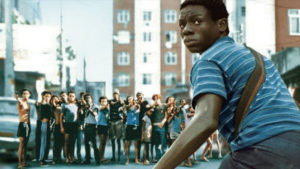

To begin with the successes of the film, it is clear that Cidade de Deus adhered to a sense of authenticity. For example, although not in the real City of God given the extreme dangers of doing so, the film was shot in a neighboring favela in Rio de Janeiro. Furthermore, the majority of the actors were people who actually lived in the slums of Rio de Janeiro. The amateur actors participated in an actors’ workshop for several months and worked closely with acting coach, Fátima Toledo to ensure their performance in their role was believable.

The actors were encouraged to improvise and Meirelles included suggestions from the actors as well. For example, when shooting a scene where the gang is rallying before a shootout, a young actor asked if they were going to pray before beginning the battle, as he used to do when he was in a gang. Meirelles then had that child lead the prayer in the scene. By hiring people who lived in the conditions that the film was portraying, the creators aimed to reach a level of authenticity not often reached in mainstream cinema.

Several aspects of the film seek to and succeed at bringing the audience into the gruesome and grimy reality of the favela. The sunburnt filters, off-balance camera angles, macabre portrayals and unsteady cinematography all work to evoke a general sense of distress and anxiety from the audience. The film may be described as morbid, but the purpose of the horrific portrayals goes beyond shock value.

Audiences will likely grow to relate to or appreciate the characters. As a result, when a beloved character is victim to intense violence or even murder, the gruesome depictions trigger a visceral reaction that emotionally draws the viewer deeper into the film’s reality. The film wishes to hide nothing of the massive losses of life in the City of God and the lawlessness that rules the land.

In this way, global audiences can more genuinely connect with those in extreme poverty, beyond the general sense of pity many well-off people might feel when seeing real pictures of people living in the slums. Visiting this world through film, previews for audiences, the cycle of violence perpetrated by poverty. Poverty produces a sense of fear and powerlessness, which in turn, causes an incessant and bloody struggle for power, a pattern seen throughout the world.

Yet, the film has a sense of idealism that works in hand with the macabre depictions, creating a good cop/bad cop dynamic. Keeping in mind that the role of morbid portrayals is to expose the truth and create an authentic narrative, the idealistic tendencies of the film serve to keep the audience engaged. At the end of the day, the film is meant to profit and keep an audience’s attention. For that reason, the film cannot show an incessant stream of violence and devastation without discouraging others to watch the film or severely depressing audiences during the film.

Institutional Poverty and Valid Criticisms

The film tends to rely on Rocket, the narrator and aspiring photographer, as a saving grace of the narrative. Rocket interrupts the vicious plot with his aspirations and personal anecdotes. He is only a bystander of the devastation, does not get too involved and has aspirations beyond the favela. In fact, Rocket ends up reaching his goals and becoming a successful photographer.

This is where, I believe, valid criticisms of the film begin. Assistant Director Lamartine Ferreira explains that they “wanted to show that people from the slums can lead normal lives and improve their situation if they take advantage of their opportunities” (2014).

This intention implicates a “pick yourself up by your bootstraps” tale that ultimately washes over the foundational issues of extreme poverty by spotlighting the role of the individual. No matter the efforts put in by people living in the slums, not everyone can have a success story. There are good, talented people living in extreme poverty who may never get out, not because of a lack of effort on their part but rather because of the institutions that create and sustain these conditions.

Furthermore, after the film’s release, Brazilian rapper MV Bill, a denizen of the City of God, disparaged the film for bringing no human benefit to the favela and for exploiting the city’s children. His criticisms were in fact, well founded. Though some started their acting career because of this film, the conditions of the City of God have hardly improved since then.

Additionally, the young boys who played a group of thieving, violent troublemakers called the Runts have since become a notorious gang in Rio called CV (Comando Vermelho). The cycle of violence carries on in real life. Whether or not the film influenced the formation of this gang is impossible to say for sure, but what is clear from the aftermath is that the film did not serve the city’s people.

Even the two main actors who were from the favela were more or less exploited. Alexandre Rodrigues who played Rocket and Leandro Firmino who played Li’l Zé both chose to be paid US $3,000 up-front rather than wait to take a percentage of the box office revenues, given they did not know how much the film would profit. Even at a 1% box office cut, they would have gotten 25 times more than what they received.

As is the case for many films that focus on communities in the global south, there is a thin line between exploiting the people of these communities and exposing the conditions they live in. It is plausible to say there is not line at all, that they are never mutually exclusive.

Regardless, there is a reason the film has garnered such critical acclaim. The film is able to bring audiences into its grim reality and expose the cycle of violence that racialized poverty fuels and exacerbates. The power struggles speak to the instability of the favelas and the corruption within the institutions that ground them.

To balance this, Rocket’s narrations and anecdotes soften the blow from the City of God’s harsh reality. They work together to produce a beautiful film that reveals the stories of those often erased from the mainstream western world.

The film is available to stream on Amazon Prime, iTunes, and Google Play.

Get Columns Like This In Your Inbox

To receive weekly updates like this in your inbox, subscribe to The Daily Chela newsletter here.