The Mexican American War is one of the defining moments in the history of the United States, and yet one of the most misunderstood. Almost 200 years after the fact, and five generations later, it still causes pridefulness, resentment or apathy, depending on the side you´re talking with.

But even the most indifferent on both sides of the border has something to say about this historic war. What really happened? Was it an unjust war? Did Mexican traitors sell half of their country for ambition? Did the U.S. take no man’s land, and therefore no real damage was done?

The Lone Star Republic

First it was Texas, which used to be a part of Mexico, with a “J”—Tejas. The uprising to become independent from Mexico is not strictly speaking part of the Mexican-American War. Texas happened a decade earlier. Although in 1846, when the binational war started, it was still a pressing matter between the two North American giants.

On several occasions, the U.S. had offered to buy California and other territories from Mexico, but Mexico never agreed to sell. They belonged to the former New Spain, and Mexico was still a new country trying to find its own destiny and form of organization.

From The Nueces To The Rio Grande

When the United States admitted Texas as a new state in 1845, Mexico considered it an affront. When the new republic of Texas declared that the Rio Grande would be its new border, some 120 miles farther south than originally agreed, hostilities escalated.

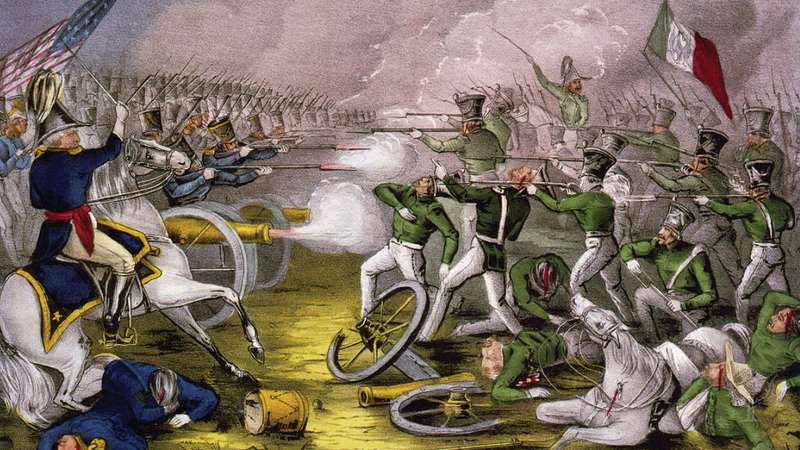

The President, James K. Polk, a Southerner, sent armed forces to the border, then at the Nueces River, expecting that Mexico would yield in the face of intimidation. In March of 1846, American troops crossed the international border and they marched down to the Rio Grande, the point where Polk wished to establish the new limit. This was a region inhabited by Mexican families. President Polk claimed that the Mexicans had shed American blood on American soil, which was not true. The US quickly declared war.

The Unjust War

The war could not have come at a worse time for Mexico: the country was indebted, politically unstable, with no real army. The Mexican soldiers were mostly poorly fed peasants, so demoralized that they often abandoned the battlefield. The United States was an industrial giant with 22 million inhabitants. Mexico was a rural country with seven million.

In only a few months, the United States annexed Nuevo Méjico and Alta California (modern day New Mexico, Utah, Nevada, Arizona, California and western Colorado). Even worse, instead of uniting against a common enemy, the Mexicans continued with their eternal divisions.

Some state governors declared themselves to be “neutral” and others refused to aid the federal government. In the U.S., thousands of volunteers rushed to be a part of the new “Mexican conquest,” dreaming of a new frontier where they could prosper with their families… and their slaves.

General Santa Anna

But not all was lost. At this time, an old General resurfaced to organize the defense of Mexico, one of the most misunderstood characters in history, the charismatic Antonio López de Santa Anna.

At the time of the war, Santa Anna was in exile. As soon as he set foot on the Mexican coast, a small crowd gathered to greet him as a hero. He immediately assembled an army from nowhere and marched north to hold back the Americans’ unstoppable advance under General Zachary Taylor.

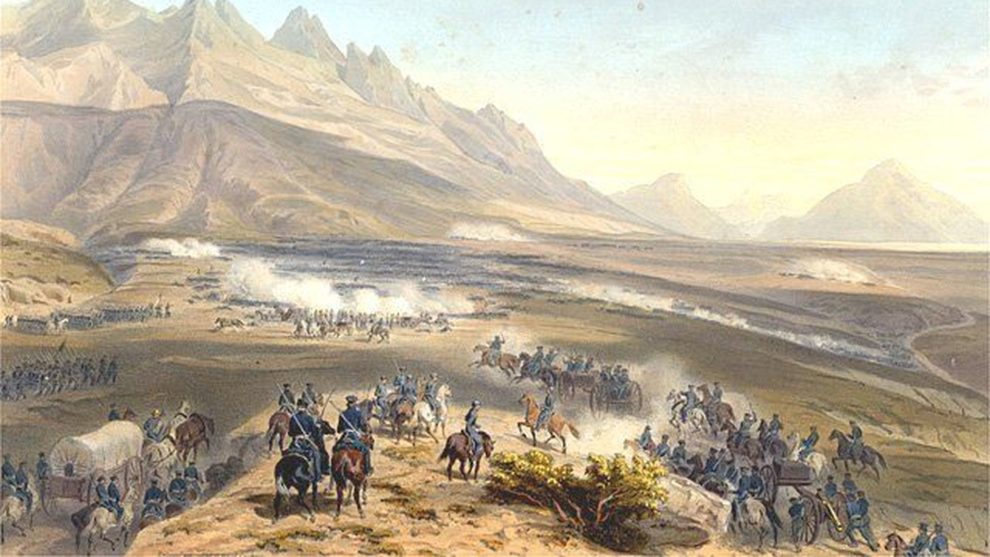

The two armies met in the outskirts of modern day Saltillo. It was David versus Goliath.

Incredibly, Santa Anna got a victory, but even more disconcerting to historians is the fact that after the heroic win at Buenavista, he withdrew from the battlefield: his troops hadn’t eaten for two days and could no longer go on.

Enter General Scott

The momentary lapse was too much for the United States, and the war shifted to central Mexico, where the Americans opened a second front. From Veracruz, valiant General Winfield Scott followed the route that three centuries earlier Cortés had taken toward the old Tenochtitlan.

At the gates of Mexico City, the church bells rang and every man and woman took a gun, a knife, a stick or a stone to make a last stand. It was September 1847. The civilian population, who had been hiding, terrified, left the houses or climbed the roofs to shoot the invaders, even children throwing stones. The jails were opened and the prisoners joined the battle.

But on September 16th, on the anniversary of Mexican independence, the Stars and Stripes waved over the National Palace of Mexico City.

The Peace Negotiations

Mexico was defeated. Many in Washington asked for the complete annexation (the infamous “All Mexico movement”) which fortunately for both countries, never happened. Mexican negotiators also saved the states of Chihuahua, Sonora and Baja California, which were on the table.

Finally, Mexico agreed —with a gun to its temple— to sign a peace treaty handing over the northern territories to the winner. It was not a sale. The 15 million dollars that Mexico received was compensation for the destruction of Mexico City, not for the land. “It was in the war, not in the treaty, that the territory that now remains in the possession of the enemy was lost,” were the words of one of Mexico’s commissioners.

General Santa Anna had nothing to do with the euphemistically called “Mexican Cession.” At the time, the Mexican president was Manuel de la Peña y Peña, and Santa Anna was chosen as a scapegoat: the new president declared him a traitor and ordered him court-martialed. His enemies did not remember that Santa Anna had volunteered to lead the army, when he could have remained sitting comfortably in the presidential chair, in the words of historian Enrique Krauze.

The “Lost Tribe”

With the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo in 1848, Mexico was reduced by half. Many Americans were distraught by what their government had done to its neighbor, including the chief negotiator in the peace talks, Nicholas Trist, who later wrote: “Could those Mexicans have seen my heart at the moment, they would have known that my feeling of shame as an American was far stronger titan theirs could be.”

The Mexican Cession raised new issues. What would happen to the Mexicans living on the conquered territories? The peace treaty stipulated that the U.S. would let them stay, give them citizenship and protect their property. It was not always the case.

But despite suffering abuse for many years, that “lost tribe” of Mexicans, managed to survive with their culture and traditions in a hostile environment. Their descendants were called “Chicanos”—a short for “Meshicanos”—and they still live in the southern United States, where they have become a positive cultural, political, and economic presence.

Get Columns Like This In Your Inbox

To receive weekly updates like this in your inbox, subscribe to The Daily Chela newsletter here.