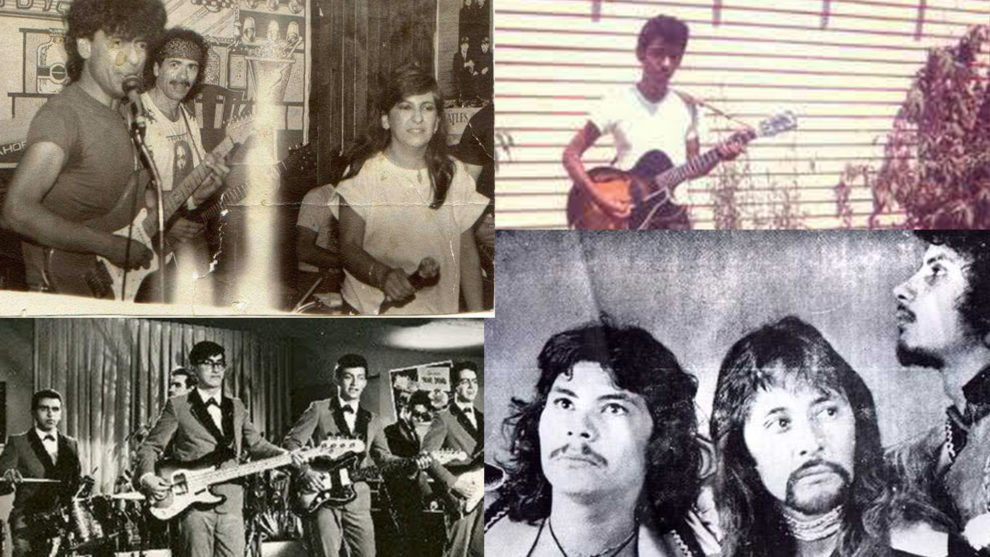

Tijuana was once to Mexican rock what the city of Hamburg was to The Beatles. It was there where, playing in seedy bars and sharing beers with California hippies, that Mexican rockers generated the movement known as “Onda Chicana.”

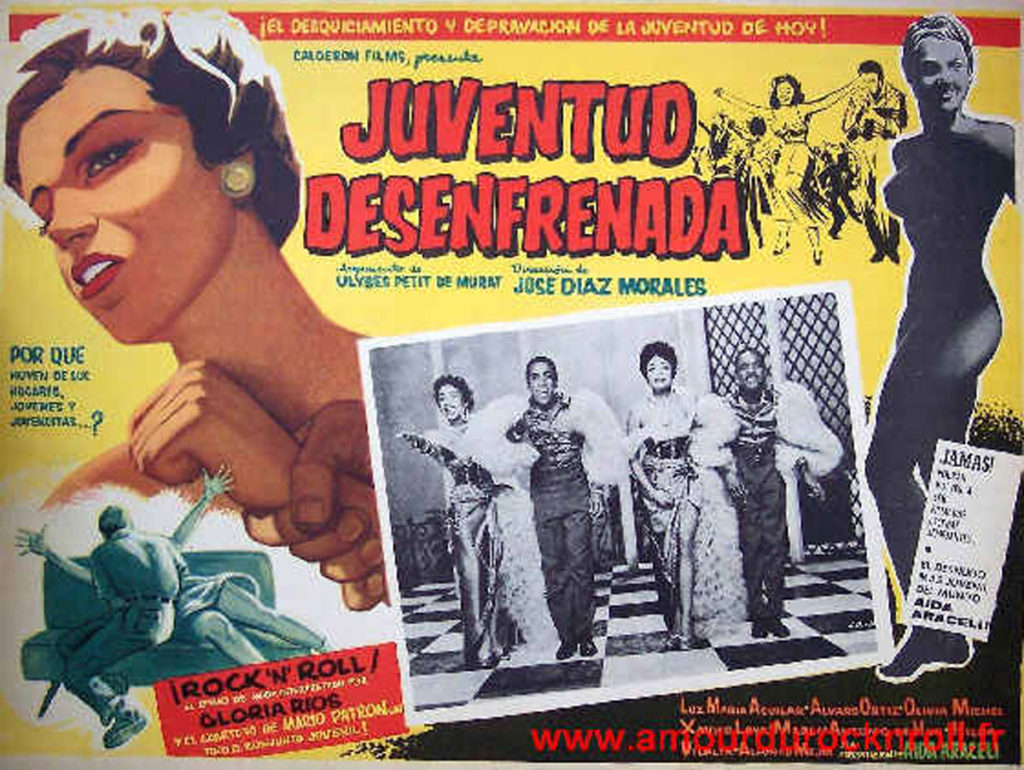

Unbridled Youth

In the mid-1950s, teenage Mexicans fell under the spell of rock ‘n’ roll, whose most visible face at the time was Elvis Presley. The screening of Juventud Desenfrenada (1956) in the country’s capital, followed by King Creole (1958), alarmed conservative parents at the time.

Although a multitude of bands emerged, covering songs by Little Richard, Elvis Presely and The Coasters, in earlier years rock ‘n’ roll in Mexico was mainly a kind of dance, not a counterculture.

Mainstream rock ‘n’ roll in the 1950s was eminently urban, from Mexico City, and its repertoire consisted of non-original songs with lyrics adapted to Spanish.

It was produced and destined for the growing Mexican middle classes.

Sanitized Lyrics

The first bands made imaginative adaptations of American Billboard hits with a message that was harmless. Los Locos del Ritmo, The Teen Tops and other talented bands, with a clean image, translated songs like “Good Golly Miss Molly,” “Jailhouse Rock,” and “Poison Ivy.”

Although the musicians themselves looked a little quirky, their lyrics were politically correct enough to be tolerated by the powers that be.

For example, Little Richard’s “Good Golly Miss Molly,” possibly about a prostitute who works long hours, became “La plaga,” about a girl who dances so well that the infatuated singer just has to take her to the altar and marry her.

“Tutti Frutti” where Richards boasts about his lovers’ romantic abilities with lascivious verses like, “Boy, you don’t know what she do to me” became, in its Mexican counterpart, a tale about a boy who offers his girlfriend ice cream of different flavors to demonstrate his love.

One of the most popular songs of the time, “Popotitos,” about a skinny girl, changed the original lyrics of Boney Morony from, “Oh how happy now we can be, making love underneath the apple tree,” to the inoffensive, “(she) dances so well that I get scared, to Popotitos I gave all my love. ”

But all that was about to change with the arrival of the Tijuana rock.

Rebirth in Tijuana

The movement was christened “Onda Chicana” probably due to the fact that the lyrics of the songs were now in English, which meant more freedom of expression.

Some thought any Mexican singing in English must be a Chicano. But bands wrote in English because they wanted greater lyrical freedom, and to sound more like King Crimson, Jethro Tull, and Led Zeppelin.

There is a reason why creativity exploded in Tijuana. Border cities have historically been sites of innovation, exchange of ideas, and artistic movements.

Due to its location near the California coast where psychedelic rock in the style of The Doors, Creedence Clearwater Revival, and Jefferson Airplane was born, Tijuana musicians managed to learn directly from the people who were playing on the other side of the border.

Many bands from Mexico City who went to Tijuana to work returned with more stamina and experience.

But the most important aspect of the Onda Chicana was that, for the first time, Mexican rock was in search of a national identity. In other words, it was trying to sound like Mexico.

Mexican Woodstock

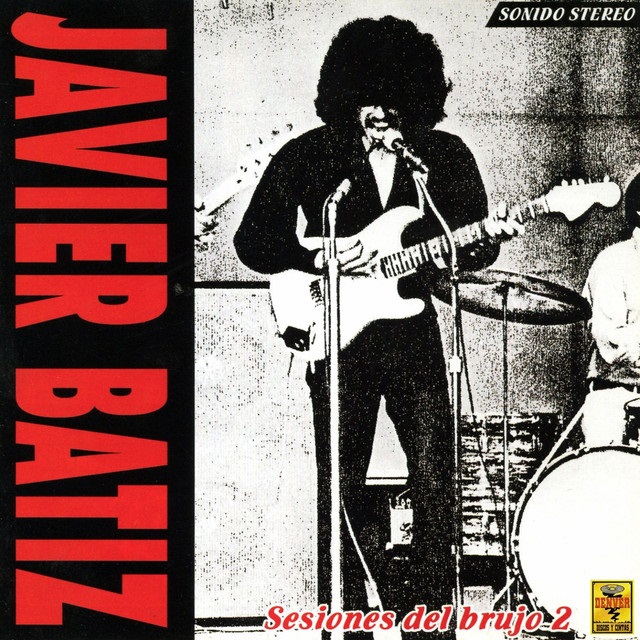

The Onda Chicana unveiled new names: Javier Bátiz, Los Dug Dug’s, Peace and Love, and many more. These people weren’t wearing sweaters, flawless hairdos, and glistening smiles like The Teen Tops or The Apsons. Most had long hair, were bearded, and didn’t even try to be nice to the cameras.

Tijuana, with one foot planted in Mexico and the other in the United States, had been able to escape the repression of the moralistic environment of the country. Writing with more freedom, in English, the Onda Chicana produced the finest rockers ever recorded in Mexico.

For example, a song with the reckless name Nasty Sex, by La Revolución de Emiliano Zapata, warns: “Can’t you see that this kind of sex is gonna let you down?” Or El Ritual’s song “Easy Woman” with lyrics that would have been unthinkable in Spanish: “I wanna-wanna touch your skin now, I wanna-wanna feel your legs now. Take it from me!”

Even with the repression that came after the Avándaro concert in 1971, an event that many have called the Mexican Woodstock, many bands of the Onda Chicana survived and continued searching for the sound of genuine Mexican rock.

Apogee and Clandestinity

Possibly the finest example in that quest was the spectacular “Stupid people,” a song by The Dug Dug’s released in 1974, where they brought the famous Mariachi Vargas de Tecatitlán into the studio.

The lyrics superbly illustrated the youth’s resentment in the era of repression after Avándaro: “I got a frustration with all my whole nation,” Armando Nava sings, and openly denounces: “I gotta say this, you’re stupid people. Change! Change!”

Supported by a fantastic blend of rock and Mariachi instruments, it would take years for Mexican rock to reach these heights again.

The irruption of the romantic ballad and dance music in the 70s and 80s sent rock almost to oblivion, with only a few exponents carrying the torch, until finally, at the end of the 80s a broad and fresh movement finally resurrected the genre, called “Rock en Tu Idioma.”

With new bands like Caifanes and La Maldita Vecindad, Mexican rock was able to re-emerge from beneath the ground.

The road to a national identity was not easy. It took decades in search of a national sound, free of censorship. But it was in the city of Tijuana, with its refreshing North American influence, where the cornerstone of Mexican rock was laid.

Download The Daily Chela TV App

Download the new Daily Chela TV app on Apple IOS, Android, or Roku.