Over the past several years, few issues have managed to capture both the nation’s attention and outrage quite like the epidemic of police brutality and misconduct, a scourge on our society that takes place in nearly every major city from coast to coast all across the United States.

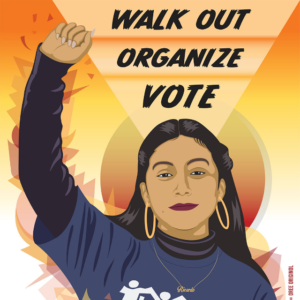

This renewed scrutiny of police violence and the very nature of policing itself has given rise to new mobilizations and civil-rights groups such as the Black Live Matter movement, with millions taking part in demonstrations over the deaths of hundreds of men, women and children (overwhelmingly from black and Latino communities) who have been killed by police.

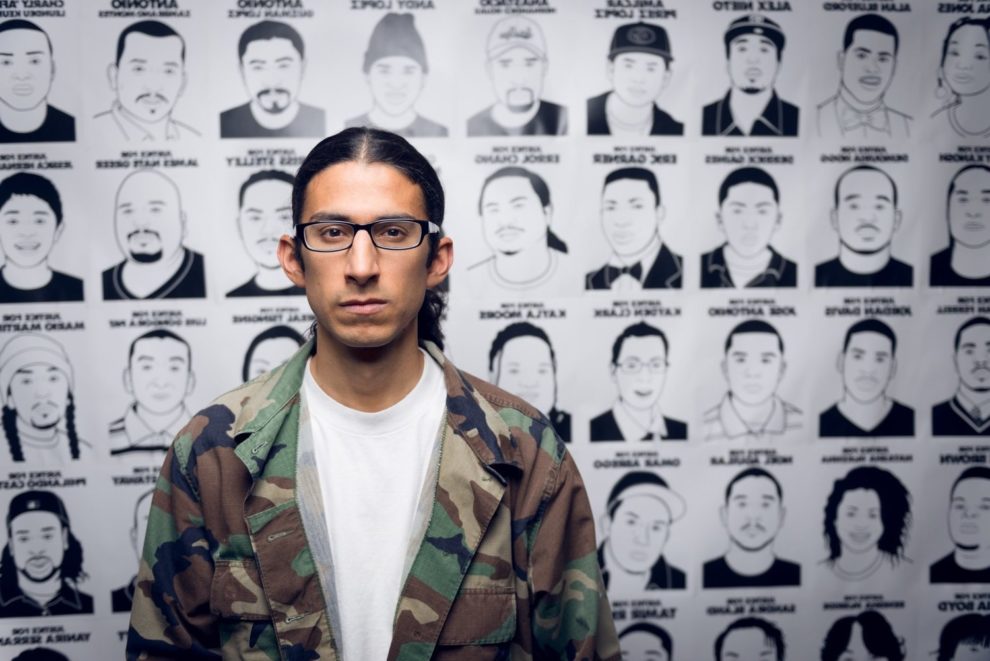

If you have attended any of these protests, then chances are you’re familiar with the art of Justice for Our Lives, an open source digital portrait series of people who have been unjustly killed by U.S. law enforcement.

L.A. Graffiti Culture

While not exactly a household name, if you’ve attended or even seen any of the thousands of protests against police brutality that have sprang up over the past several years, chances are you’ve probably seen at least some of his work without even realizing it.

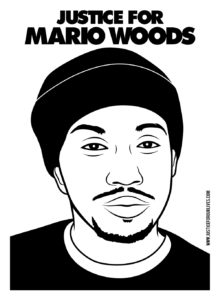

Underscored by its simplistic yet powerful designs of stark black and white illustrated posters, these portraits have become sad, ominous fixtures in wake of recent police shootings, honoring people whose lives were taken at the hands of state violence.

These portraits are the work of Oree Originol, the alias of the thirty-five-year old Chicano visual artist from Northeast Los Angeles behind the Justice for Our Lives campaign.

For the past decade, the Los Angeles born artist has made Oakland California his home, with the greater Bay Area having served as his base of operation where he has spearheaded the campaign fighting for justice against police brutality and other forms of state sponsored terrorism.

As a teen, Oree grew up immersed in the graffiti culture of Los Angeles, and it was the gang culture in his neighborhood that inspired him to seek recognition as a graffiti writer.

Oree recalled his experiences growing up in Northeast L.A. “Back in those days there were a lot more gangs in my neighborhood,” Oree said. “Growing up in the hood gave me a little bit of that edge; and my experience growing up in that environment, seeing how my friends had to deal with police encounters informed me a lot, especially how that led into me becoming an activist”.

It was also during this time that he began tagging under the writer name of “Orejas,” the Spanish word for ears and a diminutive nom de plume that made light of his large ears as a youth.

“Tagging was really the only kind of art that I was able to explore, just having my markers or a spray can, using the streets as a studio because I didn’t have one myself at home or any space to do any of that.”

Oree further explained how events in his neighborhood influenced the modern incarnation of his alias. “On one occasion, my friends and I were walking down my street and I was busting a tag on this streetlight post, and I only got to ‘Ore’ when one of my neighbors came out and yelled at me to stop. The tag remained and friends would see it, so from “Orejas” they started calling me ‘Ore’ (pronounced Or-Ray) and it became this inside joke we had amongst my friends in the neighborhood.”

Police Brutality

In late 2009, at the age of twenty-four, Oree left L.A. and re-located to the Bay Area, where he moved into a friend’s art studio, Pueblo Nuevo Gallery in West Berkeley. Coincidentally, he had moved there just months after the death of Oscar Grant, an unarmed African-American man who was filmed being shot to death at the Fruitvale BART station by BART police officer Johannes Mehserle.

Taken aback by the organization and volley of protests that followed Grant’s death, Oree recalled the stark contrast between the social and political fabric of the Bay Area and L.A.

“I remember one of the main things that

really struck me when I moved out here was the activism challenging police brutality

or in this case, a police-killing, which was very high profile at the time,”

Oree said. “It was the first video that went viral of somebody being killed by

the police and that really left an impression on me moving out there right

after, seeing all the protests eventually motivated me to do the type of work

that I’ve been doing since then”.

Originally called “Our Lives Matter,” Oree began work on what would eventually

become Justice for Our Lives several

years later at the beginning of 2014 after attending the 5th New Year’s Day

memorial gathering for Oscar Grant at the Fruitvale BART station.

“Every year I go to the vigil because I’m based out here in Fruitvale. I came from the vigil and I decided to do a portrait of him really quick and put it out there.”

Oree posted Grant’s portrait online using the #blacklivesmatter hashtag, which had been gaining popularity on platforms like Twitter after George Zimmerman’s acquittal for the fatal shooting of Trayvon Martin trial.

Over time, Oree began creating more portraits of victims of police violence, primarily using social media to share the portraits that he created for Justice for Our Lives throughout 2014. However, his artwork began gaining more attention in the summer of 2014 after the deaths of Eric Garner in New York City and Mike Brown in Ferguson, Missouri—the latter which sparked days of unrest in the St. Louis suburb.

In the following months, Oree’s portraits would become regular fixtures at various Black Lives Matter protests throughout the country against police brutality and violence. Oree recalled the campaigns gradual growth saying, “I did another design and another design and before I knew it, I was working on a project that people were engaging with and it grew little by little.”

Justice For Our Lives

Since 2014, Oree has completed seventy-five portraits honoring victims of police violence such as Tamir Rice, Freddie Gray, Walter Scott, Sandra Bland, Philnado Castile, Botham Jean, Atatiana Jefferson and dozens of others unjustly killed by law enforcement.

While many of those memorialized in the Justice for Our Lives campaign are victims of police violence, Oree said that the campaign’s emphasis is by no means solely focused on one community or event.

In fact, many of those memorialized in Justice for Our Lives, such as Anastacio Hernandez-Rojas, Valeria Munique Tachiquin-Alvarado, and Claudia Patricia Gomez-Gonzalez, along with many others, are in fact victims of state violence committed by U.S. immigration and customs personal.

“Even though I decided I would only tell the stories of people killed by law enforcement, it wasn’t just necessarily people killed by police, but also the border patrol and ICE, to express how this is an issue of state-sponsored violence.”

Not wanting to limit the campaign’s focus, or make it too broad, Oree made the decision early on to make Justice for Our Lives focus on violence perpetuated by all branches of U.S. law enforcement.

“Primarily my intent was to address police violence, but, it’s not just necessarily a police issue or only the border patrol,” Oree Said. “It’s produced by a system that where the state is funding this and attacking us and we as the citizenry are paying for these military weapons that the police and border patrol now have”.

While concerns about the militarization of local law enforcement and police brutality are still at the forefront of many black and Latino communities, in 2020, unless you have been closely following specific stories, you’d probably be hard-pressed to recall the name of a single victim who has lost their life at the hands of police violence in the past several years.

That’s not to say that police brutality and misconduct in the U.S. has fallen. In fact, some research suggests the opposite. Yet amidst this chaos, it seems that police shootings and brutality that would have garnered national attention in the past, are now mere blips that hardly manage to register a response in the midst of a tsunami of Trump-related coverage.

Oree voiced his frustration at news medias’ lack of coverage regarding police violence in the years following the 2016 election. “As soon as Trump came into office, that’s when I noticed how the focus went away from police brutality to immigration, and all of these other scandals we’ve been dealing with under a Trump administration,” Oree said.

While news media has largely turned a blind eye to police violence and allowed coverage to go wayside in wake of Trump’s election, for many communities across the country, police violence and misconduct is a constant never-ending cycle that has relentlessly ravaged families, neighborhoods and entire communities.

“I’m sure that the numbers have risen now with these kinds of instances, we just don’t hear about it because we’re hearing about impeachment or the next war we’re on the edge of.”

Now, nearly six years removed from Justice for Our Lives’ inception, in an era where police brutality and racially motivated violence only seems to be increasing, Oree reflected on the growth of the campaign and the work that still remains to be completed.

“It’s fulfilling to know that I’ve produced something that has been a tool for people in the movement to be able to continue telling these stories,” Oree explained. “It made me realize the importance of bringing the community together in order to solve these problems.”

Since 2014, Oree has completed seventy-five portraits with plans to cap the project at a hundred portraits. Upon completion, he hopes to compile his artwork into a book complete with testimonials from organizers, activists and family members of those memorialized in the portraits.

While Oree has set no timetable on the conclusion of Justice for Our Lives, Oree remains committed to seeing to the end. “This has been a project that has brought me down in ways that I didn’t expect, it’s a sad story there’s nothing positive that you can take from the actual loss of life.”

However, in spite of the obstacles that remain in a nation still struggling to reckon with enacting true comprehensive police oversight, racial justice and criminal justice reform, Oree remains optimistic in the community’s ability overcome, and ultimately bring about, the change that is so desperately needed.

“Having the community come together is the only real way we’ll be able to heal and bring justice, however that materializes. And although the work still continues of course, there is no real justice unless the community comes together.”