Pressures for Latina/os to assimilate to American life have been both implicit and explicit throughout history, either through societal culture or institutional measures. In terms of the United States educational system, these pressures manifest themselves in the way Latino/a students are treated even to this day.

As countless examples throughout history illustrate, the aim of the education system has seemingly been to “Americanize” their students, modeling them after an ideal citizen and exorcising cultural differences that might deter them from acting as such.

Of course, in the modern day, these intentions are muffled and minimal, but there is importance in understanding the history of the educational experiences for Latina/o students in the United States. Understanding history will help mobilize efforts for educational improvement in the present.

Though public understanding tends to tie educational segregation to the black civil rights movement, Latina/o communities played a notable role as well. In fact, Alvarez vs. Lemon Grove School District marks the first successful desegregation court case.

During the Depression era, both Latino/a immigrants and specifically Mexican-American people were severely scapegoated and characterized as “illiterate, diseased, pauperized Mexicans” as writer Kenneth L. Roberts describes in a piece written for the Post in 1928.

Lemon Grove Incident

The Lemon Grove incident embodies U.S. efforts to curtail the presence of ethnic differences. San Diego’s Lemon Grove case was a response from Mexican/Mexican American parents outraged by the segregation of their children.

The school they were allowed to attend were termed “Americanization schools” meant to correct “the deficiencies of the children of Mexican descent… [thereby] avoiding the deterioration of American students as a result of contact with the Mexicans” as researcher Robert R. Alvarez explained in his study of the incident .

In reality the severely underfunded schools were meant to enforce white standards and curtail their Spanish literacy. The school board aimed to make the Mexican-American children more aligned to the white standard, through “Americanization” but while doing so, implied through the children’s separation and the depleted educational resources, that they were second class.

Enraged parents and a legal counsel formed the Comite de Vecinos de Lemon Grove (the Lemon Grove Neighbors Committee) and with the ruling of an empathetic judge, Claude Chambers, were able to win the case, undoing the segregation of their schools.

Mendez vs. Westminster

In 1947, the Mendez vs. Westminster case shows that the efforts to “Americanize” Latina/os students were still not subdued.

In a first-hand account, Alicia Vidaurri Anaya, a white passing Latina student at the time, explained that the children were turned away simply because they looked Mexican, not based on their language or nationality. Latina/os were pushed into an underfunded school that was located next to a farm and electric fence that could electrocute students if they touched it.

Paving the way for the Brown vs. Board of Education case, parents Gonzalo Mendez and Puerto Rican activist Felicitas Alvarez (her surname through marriage was Mendez), and attorney David C. Marcus, led a class action suit backed by other parents, some of different school districts.

Though George Holden deputy Orange county council argued the separation was due to English unproficiency, there was likely hidden xenophobia in the school district’s mission to Americanize the children. In fact, the Garden Grove School District Superintendent at the time held obvious biases.

In his 1941 master thesis he wrote about the separation of Mexican students in which he described Mexican students as “of less sturdy stock than the white race,” as lacking “personal habits of hygiene,” and of “poor mental attitudes.”

Attorney Marcus used education experts and sociologists who stated that desegregation would help the children become integrated and “Americanized” to win their case.

Though desegregation is a step towards liberation of Latina/os, an apparent criticism of the case is that they promised students would assimilate to white standards which fulfilled the American mission to erase the identity of Latina/o people, to make them more American.

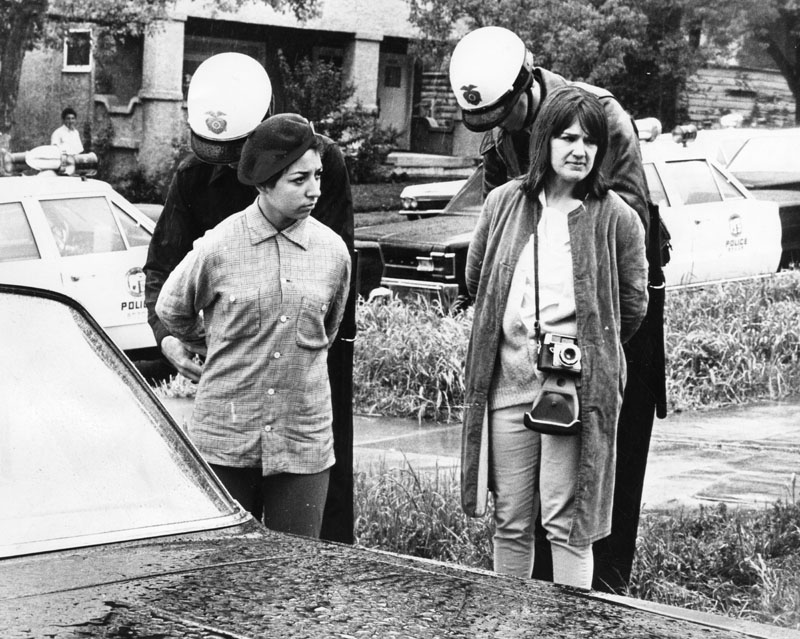

East L.A. Walkouts

In the 1960s, sometime after the Mendez case, the East L.A. movement began taking form. The schools, though desegregated, were in an area where the student body was still predominantly Latina/o.

The learning environment was “deteriorated” and overcrowded, and the staff and school board were largely bigoted as Haney López describes in his 2003 essay. In the film, Chicano! Taking Back the Schools (1996), Harry Gamboa describes an instance in which he was led to the front of the class and shamed for being a monolingual Spanish-speaker.

This story echoes a theme communicated throughout history; that having Latino roots made one “less than” their white peer. It is interesting to note that the language which was once forced upon Latina/o ancestors by white European imperialist powers, is now used by white Americans to demonize them.

Another form of injustice in this case, the tracking process, socialized and pushed Latina/os into more manual work industries instead of higher education. All of these practices not only parallel the segregation and “Americanization” of Latina/os in earlier cases like Lemon Grove and Mendez vs. Westminster, but also show how the methods become more dynamic and discrete.

The middle and high school youths were “Americanized” through tracking them into blue-collar jobs (to utilize them as a working class), but degraded to second class through the bigotry of their staff, the demonization of their language and culture, and the failure to provide them with resources for higher education.

Mexican American/Raza Studies Program

In reaction to the conditions of the East L.A. school conditions, the youth organized blowouts/walkouts that centered around the students’ “grievances, all [the] things that are wrong in the school” as Sal Castro, a teacher and counselor who supported the students’ movement, explains. This event is an example of Latina/o mass alignment to combat injustice but in this case, the battle shifts to the youth.

The Tucson Unified School District’s elimination of the Mexican American/Raza Studies Program (MAS) in 2012 presents itself as a more contemporary example of the “Americanization” mission.

The film, Precious Knowledge (2011), showcases how influential the supplemental class was, correlating with a rise in graduation and grades. Superintendent of Public Instruction, Tom Horne’s campaign to shut the program down should be understood as a colorblind policy. The video shows how Horne hid under a guise of an American quest for equality to rationalize why he wanted to shut the program down.

The MAS program can be seen as a dynamic method of resistance in of itself since it performed within the educational institution, instead of against it (during its existence). This program advances the visual and political methods of resistance into the educational institution.

The defeated MAS program comments on the pervasive and lingering effects of the Anglo mission to “Americanize” Chican@ people and thereby, subvert their power and sense of identity.

Thankfully, the future beholds many opportunities for improvement. In 2017 Federal Judge A. Wallace Tashima ruled that Arizona showed discriminatory intent in shutting down the MAS program. Furthermore, ethnic studies programs in public education has continue to gain popularity across the nation.

To explain the ideology of Anglo-led “Americanization” and pressured assimilation simply: a copy will never be as “valuable” as the original; the copies only ensure how powerful and dominant the original is.

Though there is an apparent shift, the historical mission to “Americanize” Latina/o students can evolve to covertly achieve its goal. Pressured assimilation is embedded within U.S. culture and therefore as a community that is constantly under cultural attack, Latina/os must be wary, observant, and ready to mobilize to combat any attacks on Latina/o and their sense of self.

Everyone has the power to inflict change. From students to parents to educators to the general public, we all have the opportunity to drive improvement, both from inside the systems and outside of them.

Get Columns Like This In Your Inbox

To receive weekly updates like this in your inbox, subscribe to The Daily Chela newsletter here.