Last week, I wrote a column criticizing UCLA’s decision to change the name of the Chicano Studies program. The column garnered a fair amount of attention, a few respectable rebuttals, and a whole lot of predictable name calling (my personal favorite was that I was a “racist spic”).

One response appeared at Remezcla. In the column, scholar Ester Trujillo argued, among other things, that Central Americans are a fast-growing population who are merely utilizing and building onto the “solid institutional foundations” that Chicanos have already created.

The column touched on multiple subjects. But while I agree with some points, I disagree with other points and the logic used to reach those points. So in the spirit of ongoing discourse, I want to offer some additional perspective on not only why Mexican Americans are so protective of Chicano history, but why so many Mexican Americans are unhappy with academia and media.

Changing Demographics?

In the piece, Trujillo suggests the demographics of L.A. are swiftly changing. However, context is important. While the Salvadoran population has certainly increased over the years, roughly 78% of Latinos in Los Angeles are still of Mexican descent, compared with 8 percent who are of Salvadoran descent.

Does this really qualify as a “demographic change?”

The rest of the nation reflects this picture. According to Pew Research, there are 36 million Mexicans in the United States, compared with 2 million Salvadorans. To put this in perspective, all of El Salvador could migrate to the U.S. and there would still be 29 million more Mexicans.

My point isn’t that one group is supreme to another. My point is that despite what some activists claim, the demographics will likely never change much because they are incapable of changing. The numbers simply don’t exist, barring entire Latin American countries migrate to the U.S. and Mexico (to which there are another 129 million Mexicans) no longer allows Mexicans to walk across the border.

“Chicano culture is more than a single march in East L.A. It is the century-long culmination of suffering, defiance, expression, and rebellion.”

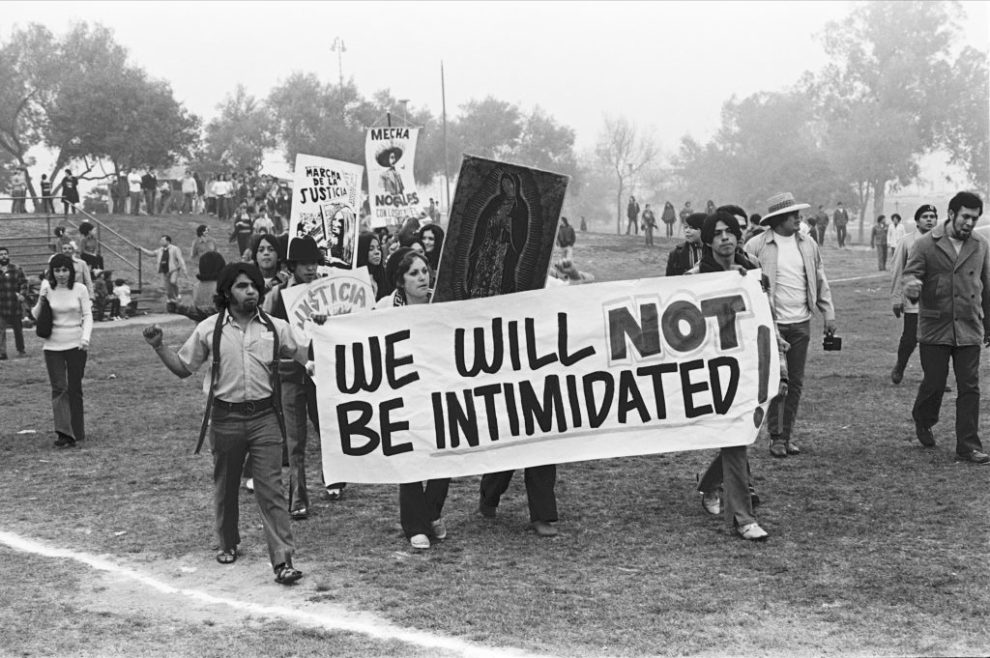

Trujillo also argues that, “When the youth of East Los Angeles marched in the Chicano Moratorium Against the Vietnam War in 1970, Central Americans were there—shoulder to shoulder.”

Again, this is true. But what are we to take from this? Walter Philip Reuther was a white man who marched alongside Martin Luther King Jr. at Selma. Does that give white people equal claim to the African American Civil Rights Movement? George Moscone was a straight man who advocated gay rights alongside Harvey Milk. Does that give straight men equal claim to the LGBTQ movement?

Of course not. All civil rights movements are comprised of a loose coalition of groups and individuals. However, just because one group marches alongside another, does not afford them a license to revise or amend the original movement. And certainly not 50 years after the fact.

Chicanos, Mexicans, and Mexican Americans

Critics have suggested that displaying pride in the Chicano, Mexican American, and Mexican identity equates to nationalism. But I suspect some of this arises from a misunderstanding of the term Chicano and the context in which the term “Mexican” is often used in Mexican American circles.

First, not all Mexican Americans self-identify as Chicano, but most Chicanos are in fact Mexican American. This doesn’t mean other people didn’t grow up with Chicanos or identify with aspects of Chicano culture. This doesn’t mean other people didn’t march alongside Chicanos. And lastly, this isn’t intended to erase or minimize the contributions of those who are not of Mexican descent. But it does mean Chicano culture is overwhelmingly comprised of Mexican Americans.

Second, both Mexican Americans and Chicanos use “Mexican” interchangeably to refer both to themselves and to each other. In this context, the word “Mexican” is not intended to promote or endorse the Mexican government as some seem to believe. Nor is the word “Mexican” always a literal reference to nationality.

I hate nationalism. I think the Mexican government is corrupt. I think the Mexican government has treated Central Americans horribly, and I think it has been complicit in carrying out Donald Trump’s backwards immigration policies that break up families and tear apart communities.

I’m far from a nationalist.

“Special interests want us to forget our histories. They want us to believe we can all be summed up with one label. But in order to achieve this, they must first pressure everybody to get in line.”

For most of us, “Mexican” is a term of endearment. It is not a literal reference to a nation. After all, most us have been called Mexicans our entire lives despite being born in the United States! This is something Central Americans can surely relate to because the same ignorant people also frequently mistake Central Americans for Mexicans. Can we all at least agree this is annoying?

Third, Chicano culture and Mexican American culture is about more than just the 1960s Civil Rights Movement. Yet for whatever reason, that seems to be the only thing academics latch onto when trying to convince people that Chicano history is open to being revised and amended.

But I would argue Chicano culture is a complex web of sub-cultures and movements. It is the Chicano Civil Rights Movement. It is the Chicano lowrider community. It is the Chicano art community. It is Chicano fashion. It is Chicano tattoos. It is pachuco sub-culture (I explain this history in a separate essay here). In other words, it is more than a single march in East L.A. It is the century-long culmination of suffering, defiance, expression, and rebellion.

Some of these sub-cultures overlap. Some of them don’t. But for better or worse, all of them were integral threads that weaved the fabric to what has become the global phenomenon known as Chicano culture, which fuses both political and social identities. Many of us are proud of this history. Many of us are proud of this heritage. And that is why many of us are so defensive and protective of it.

Identity Politics and the Woke Industrial Complex

Other critics have suggested that embracing our cultural distinctions somehow promotes division. But in a climate ruled by identity politics, how can critics have it both ways? On one hand, we are told that our intersectional distinctions should inform and dictate our daily mindset. Yet the moment one of us expresses too much pride in our distinctions, we are told we are being divisive.

And that’s the problem with identity politics. In the end, the politics always trump the identity.

I bring this up because many Mexican Americans like myself believe there is a deliberate attempt by special interests to erase the Mexican American identity in favor of consolidating the Latino community into one generic bloc under the guise of “inclusivity.”

These special interests want us to forget our histories. They want us to believe we can all be summed up with one label. But in order to achieve this, they must first pressure everybody to get in line. And Mexican Americans and self-described Chicanos to a large extent, remain some of the most vocal holdouts.

“We are told that our intersectional distinctions should inform and dictate our daily mindset. Yet the moment one of us expresses too much pride in our distinctions, we are told we are being divisive.’

I’m not alone in my rejection of these tactics. Nor am I alone in my skepticism of identity politics. Proof of this is the fact that Bernie Sanders is polling so well with Latinos. Yet special interests, academia, and media continue to push an alternative narrative on us (and no, I’m not a Bernie supporter).

Make no mistake. My original column was about more than a department name change, to which I think is largely superficial. It was about media and academia continually ignoring the majority of Latinos in this country who don’t subscribe to the endless stream of revisionism and outrage. It was about elitists trying to convince Latinos that anyone who refuses to get in line are somehow divisive, when in reality the true division among Latinos is resulting from debates such as indigenous origin and skin complexion.

You want to talk about skin? Perhaps we should talk about people who are thin-skinned, the most obnoxious, overrepresented demographic in the country. I’m not against inclusivity and tolerance. I’m against erasure and revisionism. And lastly, I’m against poisoning our communities with the mindset that they should go through life looking for a reason to be offended by everything.

Hard Conversations Don’t Have To Result In Divided Communities

Part of the reason I founded The Daily Chela is because I’m tired of the media veering away from the elephant in the room and making broad generalizations about Latinos. But this doesn’t mean I’m perfect or always right. I’m not. And to an extent, we are all products of our own experiences.

For this reason, I’m always open to changing my mind. And despite what some critics might think, I agree with Trujillo that “what unites our work is the pursuit of social justice, equity and respect for the varied experiences of members of Latino communities.” Likewise, I would add that Mexican Americans, who make up 62% of all Latinos in the U.S., have a unique responsibility to not ignore Latinos from other ethnicities who stood valiantly at their side during turbulent times.

The question is how do we achieve our shared goals without erasing any of our histories, or forcing political and ethnic generalizations on those like myself who reject them? It begins by having hard conversations like these.

Get Columns Like This In Your Inbox

To receive columns like this in your inbox, subscribe to The Daily Chela newsletter here.