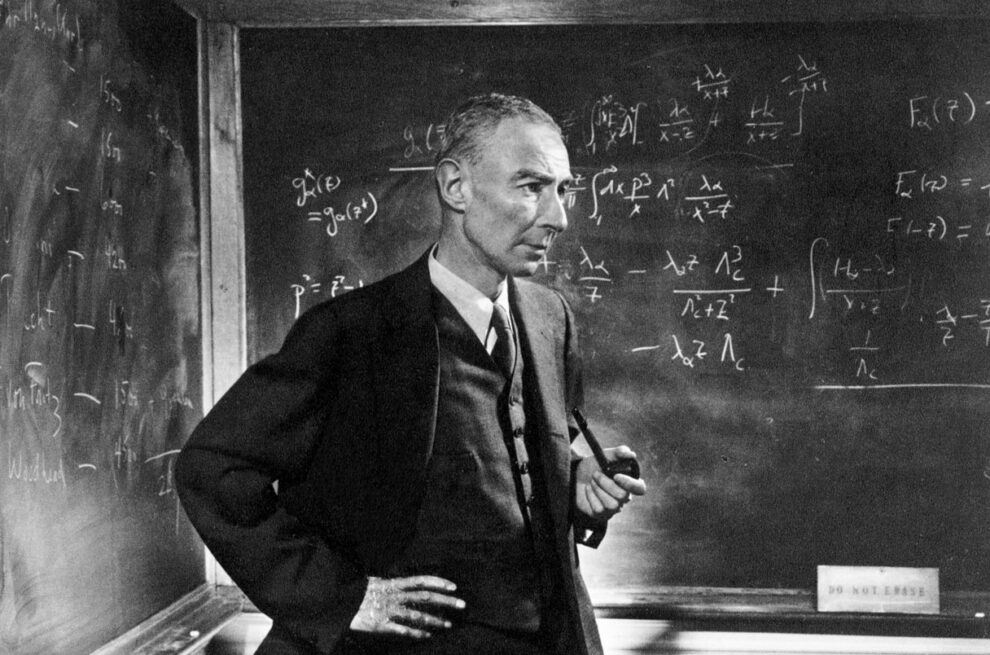

Oppenheimer is saturated with moral ambiguity, but what it is not saturated with is New Mexicans. This is particularly striking for those New Mexicans downwind of the first Trinity test in the state’s south, people who are just now being recognized for still struggling with adverse health effects of the bomb and have not received apologies or compensation for their sacrifice.

The government abdicated responsibility for this injustice, but that doesn’t diminish the film’s greatness, nor does it confer upon Christopher Nolan a responsibility to do anything but tell the story he wanted to tell. Oppenheimer was a masterpiece that deserves all the accolades for telling a masterful story.

So since not every story can be told within the confines of modern cinema, here are the lesser-told stories of the New Mexicans who sacrificed heavily for this country’s survival.

A New Mexico Tale

Ninety-nine percent of this writer’s family was in New Mexico when the U.S. entered WWII. They were in Belen, Los Lunas, Albuquerque’s South Valley, and as far north as Tierra Amarilla. My grandpa, Donald, was lucky enough to be working security in the Army at White Sands after having had surgery for appendicitis and thus avoiding having to go to the Philippines and becoming a victim of the Bataan Death March.

Two months after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor and the U.S. entered WWII, my father was born in Albuquerque. His early childhood revolved around him living with his mother and grandmother on the family’s South Valley farm, watching Mama Clara cut the heads off chickens and eating green-chile sandwiches. There was no running water, no electricity, and few men were around in those days, just a new world advancing beyond anyone’s imagination.

These people, heirs to Spanish land grants, were never anywhere close to wealthy, but they always had enough resources to live a comfortable life. While the still-young state of New Mexico had begun to modernize, it didn’t seem like New Mexico could ever truly change that much. Until World War II continued to escalate.

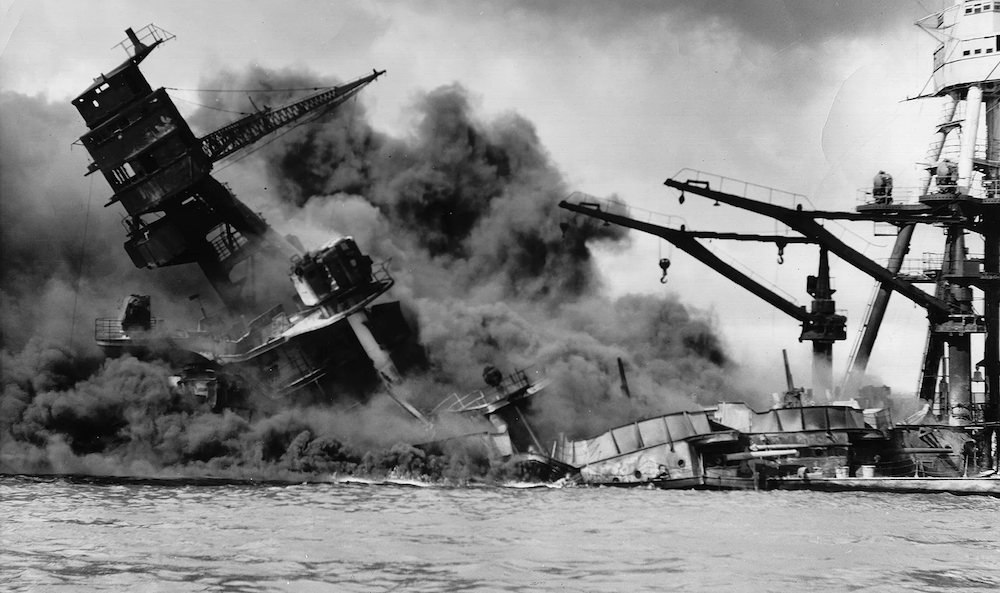

The Bataan Death March

Early in the Pacific theater of WWII, in the beginning of 1942, thousands of American and Philippine forces who were starving and rapidly running out of materials and munitions were forced to surrender to the Japanese. The result was the Bataan Death March, an infamous case of brutality against prisoners of war that lives on forever in our collective psyche.

Many of these soldiers were New Mexican, given that the New Mexico National Guard had two regiments there. Forced to march through jungle, many were enslaved. Three of my father’s “uncles” (his mother’s cousins) were in WWII—one in the Navy, one as a Marine, and one in the Army at Bataan. This man, Albert Herrera, was taken from the Philippines and sent to mainland Japan where he worked as a slave in coal mines for years until the Japanese surrendered.

When he was freed, he weighed a hair above 100 pounds. His brother Ramon, the Marine, fought the Japanese throughout the Pacific for the duration of the war, eventually getting wounded in Okinawa and then serving on occupation duty after he recuperated.

Guy Gabaldon

In one of the most heroic efforts of World War II, Marine Guy Gabaldon single-handedly captured and persuaded more than 1,000 Japanese soldiers and civilians to surrender, undoubtedly saving scores of lives by convincing people to choose peace. Gabaldon grew up in East LA, where he was de facto adopted by a Japanese family that taught him the language.

A movie was made about Gabaldon, in which a tall Anglo actor played him, which Gabaldon was reported to get a kick out of since he was short and dark. While Gabaldon himself was not from New Mexico, his family was, as he was sent to the state to spend time with his grandfather. Gabaldon is a name that’s heard in the state much more often than in California, so if you know someone with that last name, the chances are that they’re a New Mexican.

Other Sacrifices

There are the people who mined for uranium, the people who built the infrastructure for the Manhattan Project, and the people who helped keep the town of Los Alamos running smoothly during that time. Not to be forgotten, though not exclusively part of New Mexico, are the Navajo Code Talkers whose contribution to the U.S defeating the Japanese in the Pacific cannot be over-emphasized.

New Mexico’s Continuing Evolution

There’s a story, “The Farolitos of Christmas” in legendary New Mexican author Rudolfo Anaya’s book of plays—“Billy the Kid and Other Plays”– in which a Hispano northern New Mexico family is desperately trying to keep alive their Christmas tradition of Las Posadas in the midst of WWII. One character’s husband is away in the Army while she works in a support role in Los Alamos, the details of which she is not fully privy to but nevertheless necessitates her utmost secrecy.

The story’s themes revolve around these villagers having to come to terms with a changing world, and with the fact that though they’ve faithfully maintained certain traditions for centuries, they must be flexible enough to modify their practices to accommodate a new world.

New Mexico is a place of majesty and desolation, and it is also a place in which death on a mass scale became us all. The New Mexicans there, still, have endured in a harsh land full of mammoth technological and cultural changes. They have shown a selflessness that represents the best of humanity, a willingness to sacrifice both for their fellow Hispanos but also for a country that didn’t (and doesn’t) truly understand them.

They didn’t do anything earth-upending like develop an atomic bomb, nor did they come up with any new feats of engineering. What they did do was put their bodies on the line for the land they loved in ways that can inspire everyone. That’s the story Oppenheimer didn’t tell. That’s the story that we need to tell. Over and over.